In Response He Set Up the Loyalty Review Board What Was Its Purpose? Huac Stand for?

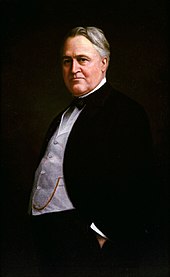

Chairman Martin Dies of The Firm Un-American Activities Commission proofs his alphabetic character replying to President Roosevelt'southward assault on the commission, October 26, 1938.

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly dubbed the Firm Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative committee of the U.s. House of Representatives, created in 1938 to investigate alleged disloyalty and subversive activities on the part of private citizens, public employees, and those organizations suspected of having either fascist or communist ties. It became a standing (permanent) commission in 1945, and from 1969 onwards it was known as the Firm Commission on Internal Security. When the Firm abolished the commission in 1975,[1] its functions were transferred to the Firm Judiciary Committee.

The committee'due south anti-communist investigations are often associated with McCarthyism, although Joseph McCarthy himself (as a U.S. Senator) had no direct involvement with the Business firm committee.[two] [iii] McCarthy was the chairman of the Regime Operations Committee and its Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the U.S. Senate, not the House.

History [edit]

Precursors to the committee [edit]

Overman Committee (1918–1919) [edit]

Lee Slater Overman headed the outset congressional investigation of American communism dorsum in 1919.

The Overman Committee was a subcommittee of the commission on the Judiciary chaired past North Carolina Democratic Senator Lee Slater Overman that operated from September 1918 to June 1919. The subcommittee investigated High german as well as "Bolshevik elements" in the United States.[4]

This commission was originally concerned with investigating pro-German sentiments in the American liquor industry. After World War I ended in November 1918, and the German threat lessened, the commission began investigating Bolshevism, which had appeared as a threat during the First Reddish Scare after the Russian Revolution in 1917. The committee'due south hearing into Bolshevik propaganda, conducted February 11 to March 10, 1919, had a decisive role in amalgam an image of a radical threat to the United States during the first Scarlet Scare.[v]

Fish Committee (1930) [edit]

U.Due south. Representative Hamilton Fish Iii (R-NY), who was a fervent anti-communist, introduced, on May 5, 1930, Business firm Resolution 180, which proposed to constitute a commission to investigate communist activities in the United states of america. The resulting committee, unremarkably known as the Fish Committee, undertook extensive investigations of people and organizations suspected of being involved with or supporting communist activities in the Us.[six] Among the committee's targets were the American Civil Liberties Union and communist presidential candidate William Z. Foster.[7] The committee recommended granting the Usa Department of Justice more potency to investigate communists, and strengthening of immigration and displacement laws to keep communists out of the United States.[8]

McCormack–Dickstein Committee (1934–1937) [edit]

From 1934 to 1937, the Special Commission on Un-American Activities Authorized to Investigate Nazi Propaganda and Certain Other Propaganda Activities, chaired by John William McCormack (D-Mass.) and Samuel Dickstein (D-NY), held public and private hearings and collected testimony filling 4,300 pages. The committee was widely known every bit the McCormack–Dickstein commission. Its mandate was to get "information on how foreign destructive propaganda entered the U.Southward. and the organizations that were spreading it". Its records are held past the National Athenaeum and Records Administration as records related to HUAC.[ citation needed ]

In 1934, the Special Committee subpoenaed virtually of the leaders of the fascist move in the Us.[nine] Beginning in November 1934, the committee investigated allegations of a fascist plot to seize the White Firm, known as the "Business Plot". Contemporary newspapers widely reported the plot as a hoax.[x] However contemporary sources and some of those involved, such as Gen. Smedley Butler, confirmed the validity of such a plot.[ citation needed ]

Information technology has been reported that while Dickstein served on this committee and the subsequent Special investigation Commission, he was paid $ane,250 a month by the Soviet NKVD, which hoped to get secret congressional information on anti-communists and pro-fascists. A 1939 NKVD report stated Dickstein handed over "materials on the state of war budget for 1940, records of conferences of the upkeep subcommission, reports of the war government minister, principal of staff and etc." However the NKVD was dissatisfied with the amount of data provided by Dickstein, after he was not appointed to HUAC to "carry out measures planned by us together with him." Dickstein unsuccessfully attempted to expedite the deportation of Soviet defector Walter Krivitsky, while the Dies Committee kept him in the country. Dickstein stopped receiving NKVD payments in Feb 1940.[eleven]

Dies Committee (1938–1944) [edit]

Bourgeois Texas Democrat Martin Dies Jr. served as chair of the Special Committee on United nations-American Activities, predecessor to the permanent committee, for its entire seven-year duration.

On May 26, 1938, the House Committee on United nations-American Activities was established as a special investigating commission, reorganized from its previous incarnations as the Fish Committee and the McCormack-Dickstein Commission, to investigate alleged disloyalty and subversive activities on the part of individual citizens, public employees, and those organizations suspected of having communist or fascist ties; even so, it full-bodied its efforts on communists.[12] [13] It was chaired by Martin Dies Jr. (D-Tex.), and therefore known as the Dies Committee. Its records are held past the National Archives and Records Administration equally records related to HUAC.

In 1938, Hallie Flanagan, the head of the Federal Theatre Project, was subpoenaed to appear before the commission to answer the charge the projection was overrun with communists. Flanagan was chosen to testify for only a part of i day, while an administrative clerk from the project was chosen in for two entire days. Information technology was during this investigation that i of the commission members, Joe Starnes (D-Ala.), famously asked Flanagan whether the English Elizabethan era playwright Christopher Marlowe was a member of the Communist Party, and mused that ancient Greek tragedian "Mr. Euripides" preached form warfare.[fourteen]

In 1939, the commission investigated people involved with pro-Nazi organizations such equally Oscar C. Pfaus and George Van Horn Moseley.[15] [sixteen] Moseley testified before the commission for v hours most a "Jewish Communist conspiracy" to take control of the United states of america government. Moseley was supported by Donald Shea of the American Gentile League, whose statement was deleted from the public record as the committee found information technology so objectionable.[17]

The committee also put together an argument for the internment of Japanese Americans known equally the "Yellow Study".[xviii] Organized in response to rumors of Japanese Americans existence coddled by the War Relocation Potency (WRA) and news that some one-time inmates would be immune to get out camp and Nisei soldiers to return to the West Coast, the committee investigated charges of fifth column activeness in the camps. A number of anti-WRA arguments were presented in subsequent hearings, but Director Dillon Myer debunked the more than inflammatory claims.[19] The investigation was presented to the 77th Congress, and alleged that certain cultural traits – Japanese loyalty to the Emperor, the number of Japanese fishermen in the Usa, and the Buddhist organized religion – were testify for Japanese espionage. With the exception of Rep. Herman Eberharter (D-Pa.), the members of the committee seemed to back up internment, and its recommendations to expedite the impending segregation of "troublemakers", establish a arrangement to investigate applicants for go out clearance, and step up Americanization and assimilation efforts largely coincided with WRA goals.[xviii] [19]

In 1946, the committee considered opening investigations into the Ku Klux Klan, but decided confronting doing then, prompting white supremacist committee member John E. Rankin (D-Miss.) to remark, "Afterwards all, the KKK is an old American establishment."[20] Instead of the Klan, HUAC concentrated on investigating the possibility that the American Communist Party had infiltrated the Works Progress Administration, including the Federal Theatre Project and the Federal Writers' Project. Twenty years later on, in 1965–1966, all the same, the committee did conduct an investigation into Klan activities under chairman Edwin Willis (D-La.).[21]

Standing Committee (1945–1975) [edit]

Democrat Francis East. Walter of Pennsylvania was chair of HUAC from 1955 until his expiry in 1963.

The House Committee on Un-American Activities became a continuing (permanent) committee in 1945. Democratic Representative Edward J. Hart of New Jersey became the committee's get-go chairman.[22] Under the mandate of Public Law 601, passed by the 79th Congress, the commission of nine representatives investigated suspected threats of subversion or propaganda that attacked "the form of government equally guaranteed by our Constitution".[23]

Under this mandate, the commission focused its investigations on real and suspected communists in positions of actual or supposed influence in the United States society. A significant footstep for HUAC was its investigation of the charges of espionage brought confronting Alger Hiss in 1948. This investigation ultimately resulted in Hiss'south trial and confidence for perjury, and convinced many of the usefulness of congressional committees for uncovering communist subversion.[24]

The principal investigator was Robert Due east. Stripling, senior investigator Louis J. Russell, and investigators Alvin Williams Stokes, Courtney Due east. Owens, and Donald T. Appell. The managing director of inquiry was Benjamin Mandel.

Hollywood blacklist [edit]

In 1947, the committee held ix days of hearings into alleged communist propaganda and influence in the Hollywood motion picture manufacture. After conviction on contempt of Congress charges for refusal to answer some questions posed by committee members, "The Hollywood Ten" were blacklisted past the industry. Eventually, more than 300 artists – including directors, radio commentators, actors, and especially screenwriters – were boycotted by the studios. Some, similar Charlie Chaplin, Orson Welles, Alan Lomax, Paul Robeson, and Yip Harburg, left the U.S or went cloak-and-dagger to find work. Others like Dalton Trumbo wrote under pseudonyms or the names of colleagues. Only about ten per centum succeeded in rebuilding careers within the entertainment industry.[ citation needed ]

In 1947, studio executives told the committee that wartime films – such as Mission to Moscow, The North Star, and Song of Russian federation – could be considered pro-Soviet propaganda, but claimed that the films were valuable in the context of the Allied war attempt, and that they were made (in the case of Mission to Moscow) at the request of White House officials. In response to the Business firm investigations, about studios produced a number of anti-communist and anti-Soviet propaganda films such as The Red Menace (August 1949), The Red Danube (Oct 1949), The Woman on Pier 13 (October 1949), Guilty of Treason (May 1950, almost the ordeal and trial of Primal József Mindszenty), I Was a Communist for the FBI (May 1951, Academy Award nominated for best documentary 1951, besides serialized for radio), Red Planet Mars (May 1952), and John Wayne's Big Jim McLain (August 1952).[25] Universal-International Pictures was the only major studio that did not produce such a flick.

Whittaker Chambers and Alger Hiss [edit]

On July 31, 1948, the committee heard testimony from Elizabeth Bentley, an American who had been working as a Soviet agent in New York. Amid those whom she named as communists was Harry Dexter White, a senior U.S. Treasury department official. The commission subpoenaed Whittaker Chambers on August three, 1948. Chambers, too, was a former Soviet spy, past and so a senior editor of Time magazine.[ citation needed ]

Chambers named more than a one-half-dozen authorities officials including White as well as Alger Hiss (and Hiss' brother Donald). Most of these quondam officials refused to reply committee questions, citing the Fifth Amendment. White denied the allegations, and died of a heart attack a few days later. Hiss also denied all charges; doubts most his testimony though, especially those expressed by freshman Congressman Richard Nixon, led to farther investigation that strongly suggested Hiss had made a number of false statements.

Hiss challenged Chambers to repeat his charges outside a Congressional committee, which Chambers did. Hiss then sued for libel, leading Chambers to produce copies of State Department documents which he claimed Hiss had given him in 1938. Hiss denied this before a grand jury, was indicted for perjury, and subsequently bedevilled and imprisoned.[26] [27] The present-day Business firm of Representatives website on HUAC states, "Only in the 1990s, Soviet archives conclusively revealed that Hiss had been a spy on the Kremlin's payroll."[28]

Reject [edit]

Democrat Richard Howard Ichord Jr. of Missouri was chair of the renamed House Internal Security Committee from 1969 until its termination in January 1975.

In the wake of the downfall of McCarthy (who never served in the Business firm, nor on HUAC), the prestige of HUAC began a gradual decline in the late 1950s. Past 1959, the committee was beingness denounced past sometime President Harry South. Truman as the "nigh united nations-American thing in the country today".[29] [30]

In May 1960, the committee held hearings in San Francisco City Hall which led to the infamous riot on May xiii, when metropolis police officers burn down-hosed protesting students from the UC Berkeley, Stanford, and other local colleges, and dragged them downwardly the marble steps below the rotunda, leaving some seriously injured.[31] [32] Soviet affairs practiced William Mandel, who had been subpoenaed to testify, angrily denounced the committee and the police in a blistering statement which was aired repeatedly for years thereafter on Pacifica Radio station KPFA in Berkeley. An anti-communist propaganda film, Operation Abolitionism,[33] [34] [35] [36] was produced by the committee from subpoenaed local news reports, and shown around the country during 1960 and 1961. In response, the Northern California ACLU produced a movie called Functioning Correction, which discussed falsehoods in the first motion-picture show. Scenes from the hearings and protest were afterwards featured in the Academy Award-nominated 1990 documentary Berkeley in the Sixties.[ citation needed ]

The committee lost considerable prestige as the 1960s progressed, increasingly condign the target of political satirists and the disobedience of a new generation of political activists. HUAC subpoenaed Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman of the Yippies in 1967, and once more in the aftermath of the 1968 Democratic National Convention. The Yippies used the media attending to brand a mockery of the proceedings. Rubin came to one session dressed equally a Revolutionary War soldier and passed out copies of the Us Declaration of Independence to those in attendance. Rubin then "blew behemothic mucilage bubbling, while his co-witnesses taunted the committee with Nazi salutes".[37] Rubin attended another session dressed as Santa Claus. On another occasion, police stopped Hoffman at the edifice entrance and arrested him for wearing the Usa flag. Hoffman quipped to the press, "I regret that I have merely one shirt to give for my country", paraphrasing the concluding words of revolutionary patriot Nathan Hale; Rubin, who was wearing a matching Viet Cong flag, shouted that the law were communists for not absorbing him as well.[38]

Hearings in Baronial 1966 called to investigate anti-Vietnam War activities were disrupted by hundreds of protesters, many from the Progressive Labor Political party. The commission faced witnesses who were openly defiant.[39] [40]

Co-ordinate to The Harvard Ruby:

In the fifties, the nigh constructive sanction was terror. Almost whatever publicity from HUAC meant the 'blacklist'. Without a chance to clear his proper name, a witness would suddenly notice himself without friends and without a job. But it is non piece of cake to see how in 1969, a HUAC blacklist could terrorize an SDS activist. Witnesses like Jerry Rubin have openly boasted of their antipathy for American institutions. A subpoena from HUAC would be unlikely to scandalize Abbie Hoffman or his friends.[41]

In an attempt to reinvent itself, the committee was renamed equally the Internal Security Committee in 1969.[42]

Termination [edit]

The House Commission on Internal Security was formally terminated on January 14, 1975, the day of the opening of the 94th Congress.[43] The committee's files and staff were transferred on that day to the House Judiciary Committee.[43]

Chairmen [edit]

Source:[44]

- Martin Dies Jr., (D-Tex.), 1938–1944

- Edward J. Hart (D-Due north.J.), 1945–1946

- J. Parnell Thomas (R-North.J.), 1947–1948

- John Stephens Woods (D-Ga.), 1949–1953

- Harold H. Velde (R-Ill.), 1953–1955

- Francis E. Walter (D-Pa.), 1955–1963

- Edwin Eastward. Willis (D-La.), 1963–1969

- Richard Howard Ichord Jr. (D-Mo.), 1969–1975

Notable members [edit]

- Felix Edward Hébert

- Donald L. Jackson

- Noah M. Mason

- Karl Eastward. Mundt

- Richard Nixon

- John Eastward. Rankin

- Gordon H. Scherer

- Richard B. Vail

- Jerry Voorhis

See also [edit]

- California Senate Factfinding Subcommittee on Un-American Activities

- Defending Dissent Foundation

- J. Edgar Hoover

- Loyalty adjuration

- Manning Johnson

- McCarran Internal Security Act

- Edward S. Montgomery

- Mundt–Ferguson Communist Registration Neb

- Mundt–Nixon Neb

- Ruby-baiting

- Subversive Activities Control Board

- Wilkinson v. United States

References [edit]

- ^ Frum, David (2000). How We Got Hither: The '70s . New York: Basic Books. p. 265. ISBN978-0-465-04195-four.

- ^ For example, encounter Brown, Sarah (February 5, 2002). "Pleading the Fifth". BBC News.

McCarthy'due south Business firm Un-American Activities Committee

- ^ Patrick Doherty, Thomas. Cold War, Cool Medium: Idiot box, McCarthyism, and American Culture. 2003, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Schmidt, p. 136

- ^ Schmidt, p. 144

- ^ "Consummate Digitized Testimonies: The U.South. Congress Special Committee on Communist Activities in Washington State Hearings (1930)". Communism in Washington State History and Memory Project. Retrieved August 21, 2012.

- ^ Memoirs, pp. 41–42

- ^ "TO SEEK ADDED Law FOR CURB ON REDS; Fish Committee Will Suggest Strengthening Powers of Justice Section". The New York Times. November 18, 1930. p. 21. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ Berlet, Chip; Lyons, Matthew Nemiroff (2000). Right-Wing Populism in America: Also Close for Comfort . Guilford Press. ISBN978-1-57230-562-5.

- ^ "Credulity Unlimited". The New York Times. Nov 22, 1934. Retrieved March iii, 2009.

- ^ Weinstein, Allen; Vassiliev, Alexander (March 14, 2000). The Haunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America – The Stalin Era. New York: Modern Library. pp. 140–150. ISBN978-0-375-75536-1.

- ^ Finkelman, Paul (Oct ten, 2006). Encyclopedia of American Civil Liberties. CRC Press. p. 780. ISBN978-0-415-94342-0 . Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- ^ "House Un-American Activities Committee". Eleanor Roosevelt National Historic Site. National Park Service. Archived from the original on May 29, 2010. Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- ^ Nightingale, Benedict (September xviii, 1988). "Mr. Euripides Goes To Washington". The New York Times . Retrieved May four, 2010.

- ^ "Sabbatum, October 21, 1939". Investigation of Un-American Propaganda Activities in the United States: Hearings Earlier a Special Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Seventy-fifth Congress, Third Session-Seventy-eighth Congress, Second Session, on H. Res. 282, &c. Washington: U.S. Regime Printing Role. 1939. p. 6204.

- ^ Levy, Richard S., ed. (2005). "Moseley, George Van Horn (1874–1960)". Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution. Vol. 1 A–Thou. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. p. 471. ISBN978-1-85109-439-4.

- ^ "The News of the Week in Review". New York Times. June four, 1939. Retrieved March four, 2021.

- ^ a b Myer, Dillon S. (1971). Uprooted Americans. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. p. 19.

- ^ a b Niiya, Brian. "Dies Committee". Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved Baronial 21, 2014.

- ^ Newton, Michael (2010). The Ku Klux Klan in Mississippi A History. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. p. 102.

- ^ Newton, p. 162.

- ^ Goodman, Walter (1968). The Commission. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- ^ "University of Kentucky archive" (PDF).

- ^ Doug Linder, The Alger Hiss Trials – 1949–l Archived August xxx, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, 2003.

- ^ Dan Georgakas, "Hollywood Blacklist", in: Encyclopedia Of The American Left, 1992.

- ^ Chambers, Whittaker (1952). Witness. Random House. ISBN978-0-89526-571-5.

- ^ Weinstein, Allen (2013). Perjury. Hoover Establishment Press. ISBN978-0-8179-1225-3.

- ^ "Office of the Clerk of the U.S. Firm of Representatives". Archived from the original on September 16, 2012. Retrieved July xv, 2012.

- ^ Whitfield, Stephen J. (1996). The Civilization of the Cold War. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ^ "Harry S. Truman Lecture at Columbia University on the Witch-Hunting and Hysteria". Harry S. Truman Library & Museum. April 29, 1959. Retrieved Apr two, 2021.

- ^ "The Sixties: Business firm United nations-American Activities Committee" at PBS.org

- ^ Carl Nolte (May 13, 2010). "'Blackness Friday', birth of U.Due south. protestation movement". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ "Operation Abolitionism", 1960 on YouTube

- ^ "The Investigation: Functioning Abolition". Time. 1961. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ Operation Abolition (1960) on YouTube

- ^ Ramishvili, Levan (August nineteen, 2010). "Operation Abolition" (blog post). Retrieved March iv, 2021.

- ^ Youth International Party, 1992.

- ^ Rubin, Jerry. "A Yippie Manifesto". Archived from the original on July xvi, 2011.

- ^ John Herbers (August 17, 1966). "War Foes Clash With House Panel in Stormy Session After Judges Lift Hearing Ban". The New York Times . Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- ^ Jim Dann and Hari Dillon. "The Five Retreats: A History of the Failure of the Progressive Labor Party CHAPTER 1: PLP AT ITS PRIME 1963–1966". Marxists.org. Marxists.org. Retrieved December eleven, 2016.

PLP brought 800 people for 3 days of the sharpest struggle that Uppercase Colina had seen in 30 years. PL members shocked the inquisitors when they openly proclaimed their communist beliefs and then went on into long sharp detailed explanations, which didn't spare the HUAC Congressmen being called every proper name in the book.

- ^ Geogheghan, Thomas (February 24, 1969). "Past Any Other Name. Brass Tacks". The Harvard Crimson . Retrieved May 25, 2018.

- ^ Staples 2006, p. 284.

- ^ a b Charles E. Schamel, Records of the US Business firm of Representatives, Tape Group 233: Records of the Business firm Un-American Activities Committee, 1945–1969 (Renamed the) Firm Internal Security Committee, 1969–1976. Washington, DC: Center for Legislative Archives, National Athenaeum and Records, July 1995; p. 4.

- ^ Eric Bentley, Thirty Years of Treason: Excerpts from Hearings Before the Firm Committee on Un-American Activities, 1938–1968. New York: The Viking Press 1971; pp. 955–957.

Works cited [edit]

- Staples, William G. (2006). Encyclopedia of Privacy. Greenwood Press. ISBN978-0-313-08670-0.

Further reading [edit]

- Works past or about Firm Un-American Activities Committee in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

Athenaeum [edit]

- Investigation of un-American propaganda activities in the Usa. Hearings before a Special Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives (1938–1944), Volumes 1–17 with Appendices. University of Pennsylvania online gateway to Cyberspace Archive and Hathi Trust.

- Usa House Commission on Internal Security Academy of Pennsylvania online gateway to Internet Archive and Hathi Trust.

- Schamel, Gharles Due east. Inventory of records of the Special Commission on Un-American activities, 1938–1944 (the Dies committee). Center for Legislative Archives, National Archives and Records Administration. Washington, D.C., July 1995.

- Schamel, Gharles E. Records of the House Un-American Activities committee, 1945–1969, renamed the House Internal Security committee, 1969–1976. Center for Legislative Athenaeum, National Athenaeum and Records Administration. Washington, D.C., July 1995.

- Ship, Reuben (2000). "From the Athenaeum: The Investigator (1954): A Radio Play by Reuben Ship". The Journal for MultiMedia History. three.

Books [edit]

- Bentley, Eric, ed. (2002) [1971, Viking Printing]. Thirty Years of Treason: Excerpts from Hearings Earlier the Business firm Committee on Un-American Activities, 1938–1968. Nation Books. ISBN978-one-56025-368-6.

- Buckley, William F. (1962). The Commission and Its Critics; a Calm Review of the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Putnam Books.

- Caballero, Raymond. McCarthyism vs. Clinton Jencks. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2019.

- Chambers, Whittaker (1952). Witness. Random House. ISBN978-0-89526-571-5.

- Donner, Frank J. (1967). The Un-Americans. Ballantine Books.

- Gladchuk, John Joseph (2006). Hollywood and Anticommunism: HUAC and the Evolution of the Red Menace, 1935–1950. Routledge. ISBN978-0-415-95568-3.

- Goodman, Walter (1968). The Committee: The Boggling Career of the House Commission on United nations-American Activities. Farrar Straus & Giroux. ISBN978-0-374-12688-9.

- Newton, Michael (2010). The Ku Klux Klan in Mississippi: a history. McFarland. ISBN978-0-7864-4653-7.

- O'Reilly, Kenneth (1983). Hoover and the Unamericans: The FBI, HUAC, and the Red Menace. Temple University Press. ISBN978-0-87722-301-six.

- Schmidt, Regin (2000). Red Scare: FBI and the Origins of Anticommunism in the The states, 1919–1943. Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN9788772895819.

- U.Southward. 86th Congress – House Committee on Un-American Activities (Dec 1959), Facts on Communism – Book I, The Communist Credo, House Document No. 336, p. 166, OCLC 630998985, retrieved October half-dozen, 2013 →75 Stat. 965

- U.S. 87th Congress – Business firm Commission on Un-American Activities (December 1960), Facts on Communism – Volume Ii, The Soviet Union, from Lenin to Khrushchev, Firm Document No. 139, p. 408, OCLC 80262328, retrieved October 6, 2013 →75 Stat. 961

Articles [edit]

- Bogart, Humphrey (March 1948). "I am no communist". Photoplay. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- "Operation Abolition", Time magazine, March 17, 1961

- Seidel, Robert Westward. (2001). "The National Laboratories and the Atomic Energy Commission in the Early Cold State of war". Historical Studies in the Physical and Biological Sciences. 32 (1): 145–162. doi:x.1525/hsps.2001.32.one.145. JSTOR 3739864.

External links [edit]

- Works by House Un-American Activities Committee at Project Gutenberg

- Works past Business firm United nations-American Activities Committee at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- History.Business firm.gov HUAC – permanent standing House Commission on United nations-American Activities

- History.Firm.gov HUAC – 1948 Alger Hiss-Whittaker Chambers hearing earlier HUAC

- Eastern Carolina Academy Libraries: The Cold War and Internal Security Collection (CWIS): HUAC

- Un-American Activities Commission The Spartacus Educational website, UK

- House Unamerican Activities Committee (HUAC) Collection: Pamphlets collected by HUAC, many of which the committee deemed "un-American". (iv,000 pamphlets). From the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress

thomaspureart1953.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/House_Un-American_Activities_Committee

0 Response to "In Response He Set Up the Loyalty Review Board What Was Its Purpose? Huac Stand for?"

Post a Comment